Grammar of the Language of Cthulhu

Home

Return to Cthulhu Introduction

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn.

dream-CVB.WHILE dead-IL Cthulhu-SBJ R'lyeh-STLV house-STLV wait-V

Dreaming, dead Cthulhu at R'lyeh waits at the house.

IMPORTANT: Although I added this after I started writing this section, I have chosen a name for the language of Cthulhu: Dzeurhka. For how to pronounce that, see under phonology. For why, see the intro.

In the previous section, I detailed pronunciation and accent. While these are critical for actually having a structure to coin words, and for making the language audibly recognizable, there's another very important part: grammar and syntax determine how information is transmitted. Without defining them clearly, there is no way to tell, for example, the order of words. In English, we can use six different formats:

- "the cat eats the mouse" (a statement about the cat eating the mouse)

- "the cat the mouse eats" (a completely different statement, this time a noun referring to a cat which, by the way, was eaten by a mouse)

- "Eats the cat the mouse?" (an old-fashioned-sounding question about whether the cat ate the mouse or not)

- "Eats the mouse the cat?" (similar, but this time asking if the mouse ate the cat rather than the other way around)

- "the mouse the cat eats" (the mouse, which, by the way as extra context, was eaten by a cat)

- "the mouse eats the cat" (a sentence stating, bizarrely, that the cat was eaten by a mouse).

All of this makes intuitive sense, and yet you couldn't name all these rules off the top of your head. In a foreign language, the rules are just that: foreign. You need to learn them from scratch. And grammar reflects how people think. The mind of Cthulhu is not comprehensible to mankind, so naturally the grammar is also different. However, it is still completely functional and can be used. Below I'll go into significant detail on how I decided on the grammar and tried to interpret what the underlying logic was that produced the sentence, "Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn." As I did with phonology and pronunciation, I'll set aside my thought process with a bar on the side, so you can skip over it easily. Unlike phonology, however, it's less obvious how to extract grammar than how to guess pronunciation from spelling. There's more room for interpretation.

To begin with, I only had two concrete pieces of information, two words that I could definitively say what they meant: Cthulhu and R'lyeh are names, so they don't translate, and I could see them in the original sentence. The first thing that immediately stood out to me was that the translation Lovecraft gave ("In his house at R'lyeh, dead Cthulhu waits dreaming") couldn't be a literal word-for-word translation because in one, Cthulhu comes before R'lyeh, and in the other, after. So Cthulhu must put the words in sentences in at least a slightly different order than English. And there are more words in the English translation than the original chant, so the words can't match up perfectly with each other.

Adjectives

My next step was to identify which word meant "dead". "Dead" is a adjective: it describes a noun. And logically, in most languages it generally comes next to the noun. So "dead" will be either immediately before or immediately after "Cthulhu". This isn't true in every language, but it is in the vast majority; even in those where it doesn't, this rule is usually at least default even if it isn't rigid. And we know it can't be "R'lyeh" because that means something else, so "mglw'nafh" means dead.

The next thing to consider is how "in his house at R'lyeh" works. "In" and "at" are prepositions, which are mysteriously absent here. While some languages let you leave those out, they typically only do that for the preposition "to", not "in". If there's no visible preposition, the next most common thing is a suffix. In Finnish, "at R'lyeh" would be "R'lyehssä" or "R'lyehllä", with -ssä and -llä acting like prepositions. However, you would expect the word to be longer in that case, because it's not only the word "R'lyeh" but also a suffix. "R'lyeh" is very short. On top of that, you would take off the suffix when translating, so there would be a small difference between the word for "R'lyeh" in English versus Cthulhu. I thought about that for a while, and couldn't figure out a direct way to get a preposition in there, and then I ultimately came up with something completely different. Although it's a known process in natural languages, I'm not aware that many constructed languages do this: I analyzed "R'lyeh" as a kind of adjective, and the language treats adjectives differently depending whether they're stage-level or individual level.

Adjectives

Are you describing a core feature of something (blue) or something it's like in the moment (wet)?

In plain English, an individual-level adjective describes a property of something, and a stage-level adjective describes a situation that it's in. Across languages in general individual-level adjectives are usually defined more strictly as a permanent, core feature of something; here, I've relaxed it (though only slightly) by allowing individual-level adjectives to describe properties: so in "the hot coffee in the cup", "hot" is individual-level because it's a feature of the coffee, but "in the cup" is stage-level because it's just a situation the coffee is in, and it might be spilled or drunk. The only language I specifically know of that explicitly distinguishes these is Russian, with what it calls the short form (stage-level: болен) and long form (individual-level: больной).

So here, "dead" is clearly individual-level, but "at R'lyeh" is more likely stage-level: he could be somewhere else, he just happens to be there. In Dzeurhka, place names can be used as stage-level adjectives to mean "at there" or "often there". Stage-level adjectives come after the thing they describe, individual-level comes before. This isn't the only instance of splitting adjectives before versus after; French puts all adjectives after the noun, unless they describe beauty, age, goodness, or size.

Individual-level adjectives describe qualities; stage-level adjectives describe temporary states. To help illustrate the difference, look at "wet". It's individual-level when describing water, because all water is, by definition, wet. Water won't be wet now but dry later. On the other hand, when describing clothes, "wet" is stage-level, because your clothes aren't supposed to be wet and they'll dry out eventually. The distinction is useful because if a cake is inherently dry, that describes a quality of the food. If it's temporarily dry (literally "cake dry", as opposed to "dry cake") it's probably a just-add-water powdered cake mix.

Case: Who did what to whom

So now, I have the beginning of a literal translation: "Ph'nglui dead Cthulhu at R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn." Exactly half of it has been explained. Now I'm in a position to start speculating about suffixes and prefixes, and other markers. On nouns, the biggest thing is to see how you know what's the subject (who does it), the object (what they do it to), and the indirect object (anything extra: I (subject) give (verb) it (direct object) to you (indirect object)). In English, as demonstrated at the top of this page, we use the order of the words (we always say the subject, then the verb, then the object), but Latin uses suffixes, which is why everything ends in -us, -um, -ae, -i, et cetera but nothing ever ends in, say, -liv. There's always a suffix for case. For how Dzeurhka uses case, see below outside of the rationale section.

Technical note: although I originally doubted Cthulhu did this, I later realized it was more likely that he did, and this just wasn't visible due to the exact mechanics of this sentence. It's complicated, and fairly technical, but for anybody deeply interested in the logic behind my choices, for reasons I'll explain later I thought something called converbs must exist, and converbs exist almost exclusively in languages with case. Although I saw no evidence of case marking, none ought to anyway, because there's no direct object, or, by my analysis, technically an indirect object either, in which condition case or lack of it doesn't reflect the language in general. Ultimately I settled on a kind of case that accounted for all this.

Quick diagnosis: if you still aren't sure what's the subject, what's the object, and what's the indirect object, here's a quick way to tell. Replace it with the word "me". If you feel like you want to make it "I", it's the subject; if "me" sounds fine, it's either the direct or the indirect object. Indirect objects usually have a preposition like "to" or "at". So in "You gave the book to her.", the book is the object, because you can say "You gave me to her.", but not "You gave I to her."

DEFINITION: An intransitive verb just happens; a transitive verb happens to something. So "sleep" is intransitive; you just sleep. But "find" is transitive: you have to find something, you can't just find. Specifically, in English and most languages all verbs have a subject but only transitive verbs have an object.

Case: Who did what to whom

In Dzeurhka noun role in the sentence is indicated with case. Specifically, in case of an intransitive verb, you leave the only noun unmarked to be completely neutral, but more often you either put it in the agentive to emphasize its agency (as in "I said so") or the objective to emphasize its passivity ("the window broke", if read literally, states that the window did it on purpose (following the same pattern as "I broke it"), but in Dzeurhka it takes the objective.). But in a transitive verb the subject and object have special suffixes. The subject is in the agentive case (the agent, as in the one acting with agency), and the object is in the objective case. The indirect object, if there is one, is in the oblique case (indirect, oblique, slightly off-topic), regardless of whether the verb is intransitive or not.

Tense and Time

Now that I've finished nouns, I can't put tense off any longer. I've been avoiding it so far, because deciding on verb tense means claiming to understand how Cthulhu perceives time, which is quite possibly impossible. So I want to state cleanly, right up front, my reasoning here: I have a structure and an implementation that I came up with. The structure, I think, is completely realistic and there aren't any strong arguments against it. My specific implementation, which deals with which tenses actually exist to fit into that structure, is almost completely of my own invention. It isn't without rationale, but it's not even remotely implied in any of Lovecraft's work. So I'll say, use my structure, my basic format for how tense actually works, but if you think the specific tenses that fit into that format aren't good or don't fit Lovecraft's style, I completely understand; you can leave out some of my tenses, or maybe add new ones, or even just strip it down to the bare bones two or three very simple tenses. I may have gotten in over my head trying to understand Cthulhu's perception of time; generally people who try that go insane.

First, I tried to think what kinds of temporal relations Cthulhu even needs to express. As his consciousness likely lasts for eons if not the entire history of the Universe, past and present may not really be meaningful to him. This idea is heavily implied in many of Lovecraft's stories. So I thought about some of the other ways that languages express time. One way I thought promising was with aspect, which doesn't say when something happened in time, but rather, at whatever time it happened, how it was distributed in time (see below). While it may still be relevant in some cases to use tense, it's likely not as essential, so you have to use a whole extra word for it.

Cthulhu, being an eternal, timeless being, does not experience time like humans do, and therefore does not use verb tenses to say when a thing happened. Instead, given that it happened sometime, a feature called aspect is used to describe how it was distributed in time at that time. In English, "I ate" indicates a completed action, but "I was eating" means that at the time in question, the action was ongoing and unfinished. "I had eaten" implies it happened as a precursor to something else: "I had already eaten when you arrived." Aspect can be very similar in some respects to the converbs described above. While it may still be relevant in some cases to use tense, it's likely not as essential, so you have to use a whole extra word for it. English is the opposite: tense is grammatical, aspect uses extra words. In Dzeurhka, aspect uses a suffix; for tense, you add a particular word before the verb, like "did", "do", and "will" in English. This isn't mandatory;an action that happened in the past doesn't need a past tense marker if it isn't essential to know when it happened. You would, though, mark tense if you're specifically contrasting it with a different tense.

Long complicated tangent: How does Cthulhu perceive time?

Feel free to skip.

I don't want to derail this whole page with a tangent on how I arrived at my decision of which tenses I chose to use; I may explain later, but at the moment I'll just quickly gloss it. As Call of Cthulhu, so far my main source, didn't provide much information on the nature of spacetime, I had to turn to other of Lovecraft's short stories. Ultimately, in large part helped by Beyond the Wall of Sleep, I cobbled together a tense for the present, the relatively recent past (past as experienced by humans, not eons ago), and the relatively near future, none of which are particularly crazy, and came up with a kind of arrow of time that went in a spiral. Personally, and I stress this is my personal idea just so that some idea is out there to build off of, I decided that based on Beyond the Wall of Sleep's emphasis on how time did not necessarily flow linearly, but obviously it does in the very short term, you can think of time as going in a kind of spiral, repeatedly coming back to the same or a somewhat similar point, but somehow not exactly the same. So millenia from now, the events of the French Revolution might repeat almost identically; but they might occur in Kazakhstan instead of France, and the king woudn't be named Louis. I propose a fourth tense for things that are far enough into the past and future that they've gone all the way around in a circle at least once and it's no longer relevant to think of past and future as different directions. And then of course there's no guarantee that higher beings such as Cthulhu even experience the same time that we do, so there may be other tenses that we can't even define.

Of course, it needn't be a perfect spiral. It could be a circle, or a square helix, or even just a chaotic meandering line. I thought a spiral had the most potential. It also hasn't been done to death.

So to quickly recap that philosophical tangent, there are tenses for past, present, future, and very distant times, plus maybe some beyond human comprehension. All of them are marked by an extra word before the verb, like English "did", "do", and "will". However, it's not mandatory; an action that happened in the past doesn't need a past tense marker if it isn't essential to know when it happened.

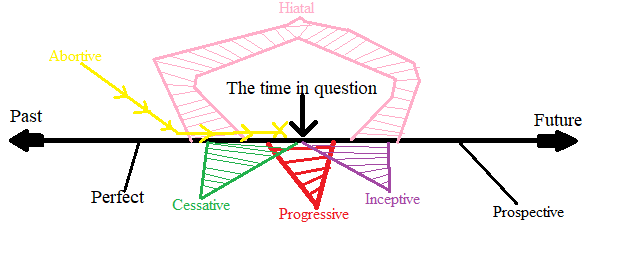

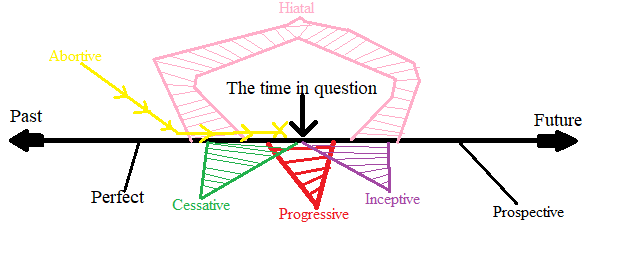

In Dzeurhka, there are eight aspects. No particular reason why those eight and only those eight; they exist because I say so. Below is a list and breakdown of each one, followed by a diagram placing them all on the arrow of time. Do keep in mind for kinds of time understandable by Cthulhu but not mankind, there may be other aspects. However, my opinion is that, because aspect isn't really where something is in time, just how it's shaped in it, then unless time can flow in multiple directions at once (we talk about the Fifth Dimension, but is that a dimension in time, like the fourth, or space like the first three?), we can probably comprehend all of them.

- Simple Aspect: Unmarked, assumed, and default. The simple aspect is like in English "I go". Not "I'm going". You don't do it now, or then, or soon, you just do it in general or habitually (I go every day.).

- Perfect: The perfect aspect is something that's already come and gone. "I had eaten" says it's already happened and in the past while I talk about something I did after I ate.

- Progressive: The progressive is what most people misinterpret as the present tense: -ing. It's for things that are actively happening in the background: "While I was talking, I started going through the cupboards." does this twice, once obviously and once subtly: it's obvious on "while talking", where talking is something I was doing the whole time that's just a background feature. Then it's used again on "going through the cupboards", where I was doing it as a continuing thing. If I said "I went through the cupboards.", that implies I started, found what I was looking for, and then stopped. That's the perfect aspect (see above). The progressive makes it more ongoing.

The progressive aspect is the most common aspect in languages, so much so that in many languages like Spanish it's considered a whole tense even though it's really not.

- Prospective: The prospective aspect is like the English "going to": it's for things expected to happen after the time in question. However, in English "I was going to do it." sort of implies you intended to but ended up not doing it. In Dzeurhka it doesn't; past tense progressive just shifts the emphasis onto the time before it happened.

- Cessative: The cessative refers to the point at which something stops happening and ceases. It doesn't imply it stopped prematurely, just that it stopped. In "As soon as she stopped talking I reminded her.", she didn't necessarily stop permanently, for the entire conversation. Maybe she did, maybe she didn't. The important thing is that she stopped and gave me a chance to say something without interrupting. Contrast this with the abortive and hiatal aspects.

- Inceptive: The inceptive is the exact opposite of the cessative. It's for when something starts happening.

- Abortive: The abortive is similar to the cessative, but not exactly. Whereas the cessative just states blandly that a thing stopped, the abortive indicates that either it had a certain end point that it was supposed to reach and failed to, or that you expected it to go on for longer. "I stopped writing when I realized my pen was broken." does this, because I apparently was going to continue writing but due to unforseen circumstances couldn't. Contrast with hiatal.

- Hiatal: The hiatal is like the abortive, but indicates that the action will resume later. It's like when you say "I stopped on my way there to look in the antique shop." You didn't stop permanently, but you paused. But that's not exactly how it works; the hiatal talks about the time while paused. If you want to talk about the pausing itself, you can use the cessative. The hiatal is while paused: "While I was stopped driving, I looked in the antique shop." Or more literally, "In between two stretches of driving...."

Converbs

Next up are converbs. Whereas English likes to use words like "while", "and", or "before", as mentioned above Dzeurhka has a different process. When you want to place an even in time relative to another event, you turn the whole phrase into a kind of adverb. "While running" becomes something like "runningly". In Dzeurhka there are six converbs: you apply them to a separate verb to the equivalent of "while doing this", "before doing this", "after doing this", "by doing this", "without doing this", and "because of this". You put a suffix on the verb, first of all: -lui in "Ph'nglui" does this. Then you move the whole thing to the beginning of the sentence (again, "Ph'nglui" is the first word in the sentence). If there are nouns, you include those before the converb: "wgah'naagl" is "waits", so if you made it a converb for "while Cthulhu waits" it would be "Cthulhu wgah'naglui...." If the verb has an aspect suffix, you put it before the converb suffix. This is a system similar to those found in Turkish or, to a lesser extent, Finnish.