Words

Now we get to the part where Ebören really starts to show as an actual functional language. Spelling is fine, but pronouncing the letter ê on its own doesn't really communicate anything. Before we can tackle grammar, there's something very important to make clear as air. Historical linguists will hate me here, but let's be blunt: English is a creole. A creole of the most mismatched languages on Earth: German, French, Greek, and Norwegian. German as the base, French from the English aristocracy, Greek from Renaissance scientists who tried to turn English into Greek and Latin, and Norwegian (technically Old Norse) from the Vikings. Creoles have to be created at a specific time, from a specific mixing of people, and English was created gradually, but functionally, English does not behave like a language of its own. One consequence of that is that there is practically no grammar. Or I should say, no inflected grammar. No suffixes, etc. We do have grammar for word order and such, but on the whole it's simpler. We completely threw out all the useful German cases, but never borrowed any of French's handy verb tenses. You'll say, "That's not true! We have the past tense, the present tense, auxiliary verbs, and something else I can't remember the name of!" Yes, we have all of that. English verbs usually have three to five forms. Spanish verbs usually have three to five hundred forms. Yes, that is a tiny bit excessive, but even thirty or forty is perfectly normal in most languages.

So, there will be significantly more grammar than English, but also the grammar is much more understandable. In English, we say "sing", "sang", and "sung", but "jump" and "jumped". In Ebören it's more like "singed". Which because there's no soft g doesn't get confused with the past tense of "singe". Nouns, like in English, don't take much of what is called inflection: the adding of prefixes or suffixes. You don't need to memorize "rosa, rosae, rosae, rosam, rosā, rosae, rosōrum, rosīs, rosās, rosīs". Verbs do inflect, but more simply than in some languages.

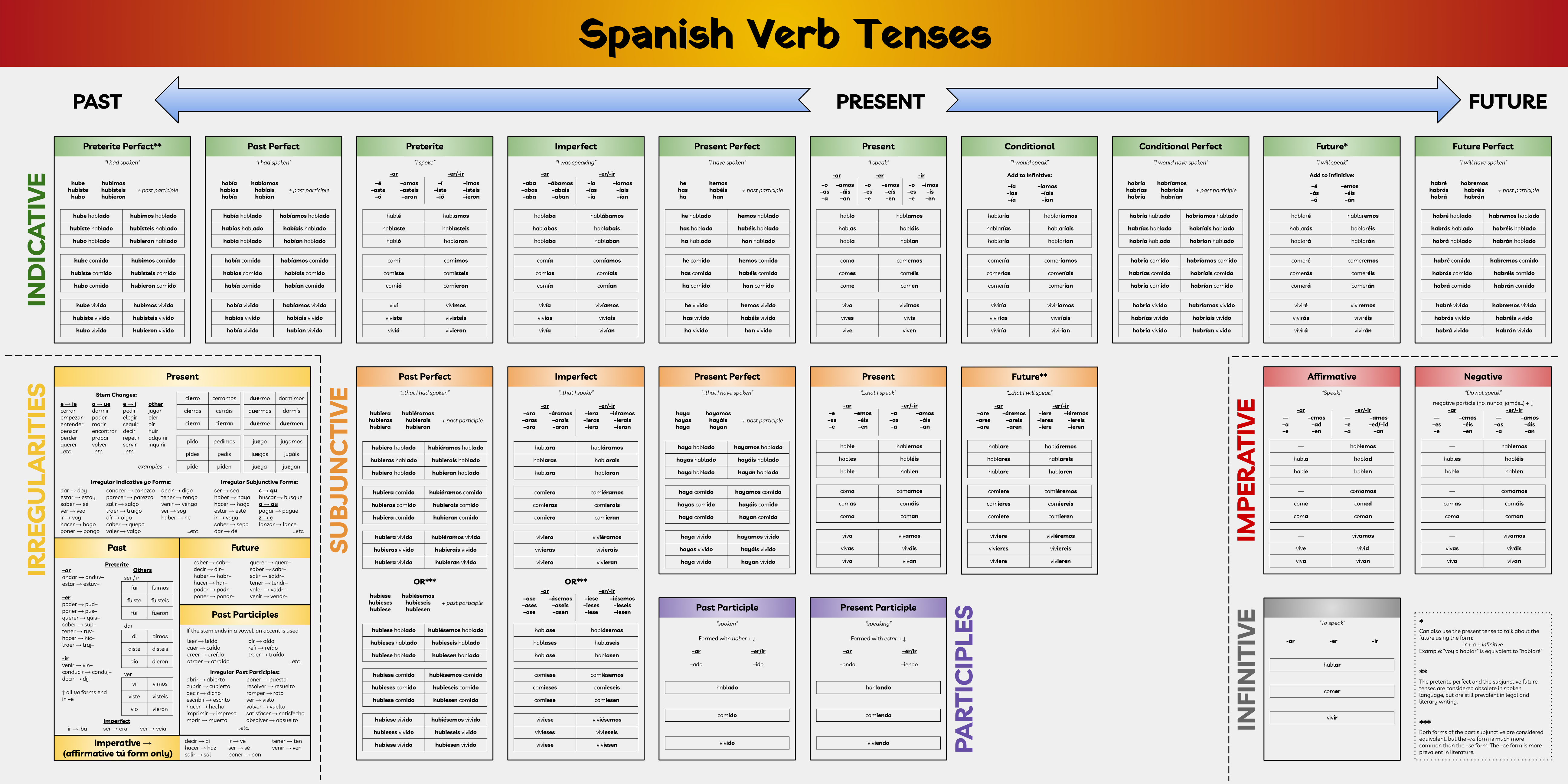

Have you ever tried to learn Spanish and gotten stuck with "hablo" versus "hablamos"? What about "olvides" versus "olvidó"? For reference here's a chart to convey some of the scale of Spanish verb inflection.

And you have to memorize all of those individually!

Ebören is a highly agglutinative language

If you actually stopped to read all of those (who am I kidding, of course you didn't read all of it) something might have occurred to you: what if instead of each of these conjugations having its own verb form, each category took a separate suffix? One for tense, one for subjunctive, etc. This is what's called an agglutinative system, and it's employed by languages like Finnish and Turkish. It is also used by Ebören. So if you have say five tenses, five moods, two aspects, and six persons (more on what that actually means below), in Spanish you would have 5x5x2x6=300 forms, but in Ebören you would have 5+5+2+6=18 forms. Clearly one is much more manageable.

I promise, we'll start using real words in just a moment, but first you need to understand something: language affects thought. You can probably understand anything as a human, but it's much easier to understand something if there's a word for it. Is it easier to remember "flat rectangle which displays images, text, and visual information electronically" or "computer screen"? So Ebören has words for some things we lack in English. The most obvious one is verb tense. In English, something happened, or it is happening. In Ebören it didn't just happen, it either happened recently or it happened a long time ago, and those are as different as past and present tense in English. If near past is yesterday, remote past could be last week; if near past is the dinosaurs, remote past could be the creation of the Universe. It's subjective, and very context-dependent, but it can also make it easier to manage thinking about time, which many languages don't address as comprehensively as space. (For example, "long" means "covering a large distance", but we call it "a long meeting", describing time in terms of space.)

All right, we can finally start making some sentences! In Ebören, you have a few words to keep track of in a sentence: the verb (what happens), the subject (who does it), the object (who they do it to), and sometimes an indirect object ("I gave the book to her" has "her" as the indirect and "book" as the direct object.). In English, we usually explain which is which by using a subject-verb-object-indirect sentence structure: "I gave the book to her", and not "her to the book gave I".

Ebören uses a SVOI word order and is strongly head-final.

In Ebören, you use subject-verb-object-indirect.EXTREMELY IMPORTANT: before the indirect oject it is essential to use the preposition ro, unless some other preposition is used instead.

DON'T PANIC! We'll use the example word "hoňjnuasmêkî", which means "Did I give it to you?" And yes, that's all one word. One sentence compressed into a word. First, if you're comfortable with a technical breakdown:

hoň.j.nu.a.smê.kî

give-1SG>3OBV.2DAT.PST.INTERR

Let's break it down piece by piece. The basic verb is "hoňjêz", meaning "to give". This is an infinitive, which is English is always a verb preceded by "to". This is a good point to mention vowel harmony. Above, we mentioned vowels and how to articulate them.

Ebören uses a front-back vowel harnmony system across whole words.

In Ebören, there are some vowels you pronounce in the front of the mouth: ä, e, ö, i, and ü. These are in the back of the mouth: a, ê, o, u, and î. Some languages, Ebören included, like words to have only front vowels or only back vowels, to make them easier to pronounce: you don't have to move your tongue as far. In "hoňjêz", "-jêz" makes it the infinitive like "-ar" in "hlablar" or "-en" in "bedeuten", but if it were "höňjêz", the infinitive would use "-jez" for vowel harmony. The infinitive is when in English you say "to do": "I want to do it", "how hard is it to do this". You preface any verb with "to".

Person: Who made it happen to whom?

Ebören uses a polypersonal agreement system applying to the subject, object, and indirect object in that order.

The next important thing is, how on Earth does the verb fit "I", "it", and "you" all into the same word? Well, in English "gives" implies a third-person subject. You can say "he gives", but never "you gives". In some languages you could drop the subject and say "gives" on its own. In English we don't like to do that because there's no provision for subject marking outside of the third-person singular, but in Spanish "hablo" means "I speak" and "hablas" means "you speak". Both of those could be a single sentence on their own—just fairly short ones.* But in both cases, the verb only agrees with the subject. In European languages it typically doesn't agree with the object. However, it does so in Georgian (the Caucasian country, not the State of America) and an obscure language called Basque spoken in the French Pyrenees (I know I said no European languages, and Basque is technically European; I mean Indo-European languages, which include the most famous ones like Italian, German, etc. and share a common ancestor five thousand years ago just how Spanish and French share the common ancestor of Latin. It's slightly complicated, but the main European exceptions are Basque, Finnish, Hungarian, Maltese, and Turkish (if you count Turkish as European to begin with). The practical upshot of that is that while Indo-European languages are roughly similar to each other (think "mother", "mater", "mutter", and "madre"), non-Indo-European languages tend to be wildly different (giving us "ama", "äiti", "anya", "omm", and "anne" for "mother"). For example, Finnish doesn't distinguish subject and object the same way most IE languages do; Turkish requires every sentence not just to be stated, but for the speaker to state how they know it to be true. The subject is terribly interesting if you're into history, even if you don't specialize in languages, and I may at some point write up a list detailing all the major branches and changes since all the Indo-European languages diverged.). The function of person is to mark relevance to the conversation: first-person is who's speaking (me), second-person is who's being spoken to (you), and third-person is who's being spoken about (her).

*Yes, I used the em dash. No, I'm not AI.

In the example hoňjuansmêkî, the j indicates a first-person subject, i.e. the person speaking or "I". The un indicates a third-person object. It could mean "him" or "her" but it doesn't make much sense to give "him" to somebody, so "it" is a much more natural reading. And finally the a indicates a second-person indirect object: "to you". This might just seem like chopping up words and sticking them inside each other, but there's a subtle advantage to marking on the verb how relevant the noun is to the people speaking: you can still have the noun explicitly marked elsewhere! The "it" above is actually what's termed an "obviative" third person: it's not immediately relevant. The proximate is nearby, say, in this room, and the obviative is, say, down the street in the neighbor's house. It's similar to the remote versus near past tenses. If I explicitly say "the book" as the object, the fact that it's obviative can clarify whether it's this book or that one. Furthermore, and even among languages that do this this is a fairly unusual detail, you can have explicit nouns in place of first- and second-person pronouns. If the verb says that I'm the one who did it, I can have the explicit subject of the sentence be something like "the president" and mean "I, acting in the capacity of president, have...." In Ebören, you always agree with nouns in the order of subject, object, indirect object, like they appear in the sentence. There are twelve suffixes to remember: four persons for the subject (given proximate and obviative as distinct persons), four for the object, and four for the indirect object. This is one of the few cases of Ebören being fusional rather than agglutinative (a purely agglutinative system would mark each personal suffix whether it described the subject, object, or indirect object, which aligns with Ebören's goals of complete transparency and simplicity; however, since this involves adding suffixes to suffixes, I think you'll agree that's going a bit far.). Unlike in English and Spanish, where "he goes" but "they go" and I "hablo" but we "hablamos", only person is marked on the verb, not number. "I" and "we" are both first person, but confusingly, English has no plural marker in the second person: "you" may be one person or many.

Tense: When did it happen?

Ebören uses past, present, and future tenses, distinguishing near and remote past and future. The suffixes for these tenses are: -jnu/-jnü (remote past) -smê-sme (near past), - (present, unmarked), -sa/-sä (near future), and -mo/-mö (remote future).

Tense is very simple; near versus remote was covered above under how language affects thought. The suffixes are -jnu/-jnü (remote past) -smê-sme (near past), - (present, unmarked), -sa/-sä (near future), and -mo/-mö (remote future). The only thing to be aware of is that like in English "I go", the present can be present, but more often it means a generic action at no specific time (e.g. "I go there every day"). You'll ask, what about "going"? Well, that isn't strictly speaking a tense; it's an aspect, which we'll look at now.

Aspect: How did it happen?

Example in English

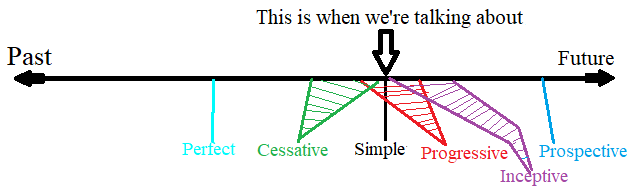

In Ebören, verb aspect is expressed with a compound tense formed with the verb to be, "kejez". "Kejez" takes all the verbal inflection such as personal agreement, tense, mood, etc. and the verb itself takes a tense marker which indicates aspect: remote past indicates perfect aspect, near past cessative, present progressive/imperfect, near future, inceptive, and remote future prospective.

A lot of people think -ing makes a verb present tense. In fact, it actually makes it the progressive aspect. "I was going" uses -ing, but it's still past tense. Adding -ing to a verb means that it has no fixed start and end, or that it doesn't happen at an instant in time. "I went" implies that you went all at once; "I was going" implies that you'll say something like "While I was going, so-and-so happened...." and for the entire event described, you had started to go but hadn't finished. This is called the progressive aspect, or sometimes imperfect (especially in Spanish).

If tense on a verb tells you when it happened, you could say aspect varies it slightly around that point in time. Technically, it's how an event is distributed in time, whether it's happening, it's already happened, it's about to happen, or whether it just happens and no further detail is required (this last is called a simple tense and corresponds to "I went", "I go", and "I will go".).

In Ebören, there are six aspects. The simple aspect, which happens more or less when the tense says it does, is just the basic tense marker. For the others, there's a breakdown below. But first, how do actually say which aspect you mean? Well, you preface the verb with "to be", which is "kejez", and you shift all the information onto that (person, tense, etc.). Then you follow that with the verb itself. It has no suffixes except a "carrier tense": it looks like it's marking a tense, but in this case the tense actually describes an aspect. In this list each aspect is listed with its carrier tense.

- Perfect: this refers to something which occured significantly before the time you mean. It's sort of like "I had done it, before the time at which....".

Carrier tense: remote past - Cessative: something that happened immediately before a time, or that went just up to then and stopped. Like "I did it until then".

Carrier tense: near past - Progressive: something that is continuing to happen. "I am doing" or "I was doing".

Carrier tense: present (unmarked) - Inceptive: it isn't happening, but at the time in question it either starts to or is immediately about to.

Carrier tense: near future - Prospective: something going to happen. Literally, exactly that, word for word: "going to do so", in the non-immediate future.

Carrier tense: remote future

One important thing to keep in mind: terminology varies across languages. The same name in Spanish and Ebören don't necessarily mean the same thing. The names are consistent within a language, but if you learn the Ebören aspects, don't be confused if you try to learn aspect in a different language and it makes no sense. For example, in Spanish perfect and cessative are not distinguished, perfect is split into multiple aspects, and there's no equivalent of the inceptive or prospective at all. This isn't just Ebören being weird; English versus Spanish commonly use different terminology as well.

If you're wondering why I keep using Spanish as an example for aspect, there are a few reasons. Part of it is that Spanish uses aspects fairly frequently, and part of it is just that I'm semi-familiar with Spanish. Although it might be more accurate to use Finnish, because Finnish aspect works similarly to Ebören aspect, I don't because Finnish has only two aspects and Ebören has six. Still, it might be useful to see an example instead of abstract descriptions, so I'll try it: in Finnish, "minä puhun" means I speak, or I am speaking, and "minä puhin" means "I spoke". "Minä olen" means "I am". So "minä olen puhunut" means "I have spoken" and "minä olin puhunut" means "I had spoken". The suffix -nut in this case isn't a tense marker, but it turns the verb into a participle. In Ebören you would replace it with a tense (specifically the remote past, if you were trying to make it perfect aspect as in this example).

Mood: Did it happen?

Ebören uses four moods: indicative, subjunctive, conditional, and imperative. The indicative is unmarked, and following tense a suffix can denote subjunctive (-ň), conditional (-s), or imperative (person agreement plus -jmon/jmön).

If everything up to now is describing what it is you're saying happens, mood explains whether it really does happen for real. The indicative mood confirms that it does; it is no marked with a suffix: if there is no reason to believe otherwise, assume every verb is indicative. The conditional says it happens if some condition is met: not "I will go", but "I would go". The conditional in English is falling out of use; one of the few ways it shows up explicitly is in "I were" (that is, "If I were, then....") as opposed to "I was". The subjunctive says that the event is not necessarily real—maybe you hope something happens, or you think it does, or you heard a rumor about it, but that doesn't make it true. Notice none of these explicitly deny that something happened; for that, you use the indicative prefaced with "fno", meaning "not". To mark a mood on the verb, after the tense suffix (or for present, which takes no suffix, after the personal agreement) add the suffix -ň for subjunctive or -s for conditional. And the last mood is the imperative, when you instruct or command somebody to do something ("Do this."). For the imperative, first you add the personal agreement (subject) on the verb for who is doing it (e.g. second-person for "Hey you, do this!", first-person for "Let's do it.") and then add -jmon/jmön.

Although it's not technically a mood, I lump in the interrogative with mood because it literally asks, "Did this happen?" At the end of a verb, after every suffix, adding -kî turns the whole statement into a yes/no question, "Is what I'm saying accurate?" And it can go with any mood, not just the indicative (e.g. "Would this be the case?"). While we're on the topic of yes/no questions, it's worth explaining how to answer the question once it's been posed. We take it for granted that you can say "yes" or "no", because you can do that in English, French, German, and most other "famous" languages. But that isn't the only way to do it. Before you complain anything else is too complicated, remember, there is a reason: the phrasing affects thought. This way has its advantages. What you do is, you ask the question, and it's always going to be a completely normal sentence, plus the question marker -kî. To answer it yes, you just parrot back the verb, minus -kî: "Does he talk? He talks." To answer no, you just parrot the verb and negate it with "fno": "He doesn't talk." The reason for this is that you really have to understand what's being said: you can't just blindly nod along saying "mm-hm, yeah, you're right." You have to actually understand what was said, and then re-say it. This is used in Irish, and it's one of the reasons why Irish has a reputation for being charmingly (or maddeningly) roundabout. In fact, there is no word for yes or no in Ebören.

The other main type of question isn't answered yes or no—it's when you ask "what" or "where" or something like that. These words work just like in English: "You saw what?" "You went where?"

Voice: Who do you blame?

Ebören uses a default active voice. The passive verbs are marked between tense and mood by the suffixe -i/îThe last thing to mention under verbs is voice. In English, we have two voices, active and passive. Active is when the subject does something, and passive is when the object does it. Voice is used to shift emphsis, so "Palestine invade Israel" is the active voice, but "Israel was invaded by Palestine" is passive. Both say exactly the same thing, but they emphasize different participants. To form the passive voice in Ebören, add -i/-î after tense but before mood.

Composing Sentences

That's all well and good, but even in Ebören, while words can sometimes say entire sentences, you do frequently need multiple words in order to make any kind of sense. You can omit "I" or "you" and leave it on the verb, but "it" could be literally anything on Earth, or off it. So you need to arrange nouns, and also things like adjectives and adverbs, which you probably studied in English class and never thought about since. Then take the sentence "I was happy that you arrived safely". What is the object of the sentence? "I am happy that..." is a verb acting on something, in this case an entirely separate sentence ("You arrived safely.") that could easily stand alone. As native speakers, you probably do this constantly without thinking; in order to compose a coherent sentence you need a firm grasp of where the words go.

Prepositions are also important, but they function pretty much as in English: "to", "for", "because", etc., all come just before the indirect object. Very simple.

Modifiers

Ebören modifiers follow their object. Ebören classes modifying adverbs as distinct from verb-modifying, in a separate class termed "modifier"; adjectives, adverbs, and modfiers are collectively termed "descriptors". Suffixes exist to convert from one type of descriptor to another: -sni/-snî (to adjective), -jeň/-jêň (to adverb), and -eläzjni/-êlazjî (to modifier).

First off, we have modifiers, which are adjectives and adverbs. Adjectives describe a noun (e.g. "house" => "blue house") and adverbs describe a verb (e.g. "I went" => "I went quickly"). Additionally, in English adverbs also modify other modifiers (e.g. "the blue house" => "the surprisingly large house"). In Ebören, both of these follow the thing they describe, so while in English you say "the blue house", in Ebören you say "the house blue", similar to Spanish where you say "la casa grande". The basis for this is that it's more important to know what the thing is than what it's like, so the noun comes first. Also, whereas in English adverbs were common historically (i.e. before the internet) but while retained in writing (for example, in this page), they're mostly falling out of use in speech nowadays, especially among younger people. In Ebören, they are completely acceptable in both speech and writing. Unlike English, Ebören distinguishes between adverbs and "modifiers" (which in Ebören has the narrower meaning of explicitly modifying an adjective or adverb rather than a plain noun or verb directly), and in a dictionary each descriptor will be listed as adjective, adverb, or modifier, but like in English, you can switch these around. In English, you can add -ly to an adjective to make it an adverb. In Ebören, the suffixes to convert to a different form are -sni/-snî (to adjective), -jeň/-jêň (to adverb), and -eläzjni/-êlazjî (to modifier).

Adjectival and Adverbial Clauses: How to make detailed descriptions

Another important thing to cover is clauses. Specifically, adjectival and adverbial clauses, which is fancy way of saying that you want to describe something but need more than one word to do it. You can say "quickly" instead of "in a manner which takes little time", but for something like "while the bread is rising", there's really no other way to say that. That is an adverbial clause, because it modifies a verb, as opposed to an adjectival clause, which modifies a noun—for example, in "the house which we visited", the house is a noun and "which we visited" is an adjectival clsuse describing it. In case you've ever wondered why we don't have a word for everything in English and have to resort to stringing together multiple words to describe one thing, this is why: you can't have adjectives for every occasion, because then you wind up with the most absurdly specific ones like this. You might be interested to know that some languages actually have tried to get around this by making single words for phrases like that. Such languages are called polysynthetic, and generally are only able to do this by interlocking words inside each other. If that sounds debilitatingly complicated, that's because it is; less than one percent of languages globally* are polysynthetic, and they tend to be very small indgigenous languages which have had thousands of years of isolation to do nothing but overcomplicate themselves. I don't speak any of them, so I can't give any examples with authority, but generally speaking they are impenetrable to foreigners. In fact, they are so much more complex that even native speakers tend to speak more slowly than in other languages to allow time to compose and understand words. Examples of polysynthetic languages include Yupik, Nahuatl, and Greenlandic, all of which you will notice are very obscure.

*No source for that, incidentally; the general impression is that significantly less than 5% of languages are polysynthetic, but there are no rigid statistics, partly because there's no official definition of a polysynthetic language.

In Ebören, adjectival clauses are formed fairly simply: first, you say the noun, then you follow it with a pause/comma (depending on whether you're speaking or writing), add "yoňa", meaning "which" or "who" or "that", and finally to actually describe what you're saying you add something like "I did it to it". So you add in a complete sentence, only replacing the noun with "it" or "he" or something like that. So in Ebören, "The house we visted" becomes "The house, which we it visited."* "The person who gave me directions" becomes "The person, which he directions gave to me."* And of course this all just describing the noun, so essentially it's still all one, multi-word noun, so you'll probably have something after it (a verb, maybe), and after this sub-sentence you add another pause/comma. That might seem slightly complicated, but it does help to place a definite boundary on things, and sort cleanly where everything belongs. English is what's called an analytic language (if you read the aside above, it's the exact opposite of a polysynthetic language), so it likes to throw all the words in the air and hope you can tell how they relate to one another. Which isn't to say there's no structure—in fact, there's arguably more, because things are so ambiguous that you need careful word ordering to clear it up—but there are often cases that could be read in different ways. The classic case is "I saw the man with the telescope; who had the telescope?" In Ebören, you would say either "I the man saw, by using the telescope" or "I the man, which he had the telescope, saw" (or more literally, "I the man, which the telescope was with him, saw."). The other thing is where in English we say "What you said was important", in Ebören you use an adjectival clause and say "It, which you it said, important was."**Remember the word order described under agglutination. The object comes before the verb, so it's "I the house saw", not "I saw the house", and from that you get "I the house, which we it visited, saw". Here you have to start juggling two or more non-English features, but you have to do that in every language; you'll get used to it.

Adverbial clauses (describing verbs) are very similar to adjectival clauses, but with the key difference that while adjectival clauses use exclusively "yoňa" for "who" or "which", adverbial clauses can use a very large number, for things like "while", "before", "after", "because", and things like that. Otherwise, adverbial clauses are formed identically to adjectival clauses, except they modify verbs.

And finally, to close off this slightly more complicated section, there's one more type of clause: we've done describing clauses, but sometimes a clause can serve as a noun. A vivid example I've seen is "That grandma was drunk surprised me"; "that grandma was drunk" is the subject of the sentence, the thing surprising me. This is done by using the Ebören word for "that", which is "hmas"

And that's it for clauses! This was easily the most complicated section so far, so if you made it through and didn't have prior knowledge or experience, congrats.

At the time of this writing (02/18/2026) that's all there is; the above content covers essentially everything necessary to operate this language.